By Omaya Sosa Pascual, Ana Campoy and Michael Weissenstein | from the Center for Investigative Journalism, Quartz and the Associated Press

After Hurricane Maria, many Puerto Ricans with treatable ailments like bedsores and kidney problems died agonizing and unnecessary deaths, according to dozens of accounts from family members. This was a slow-motion, months-long disaster that continued even as Donald Trump lauded his administration’s response to the category 4 storm.

The chaos that followed in Maria’s wake changed the face of death in Puerto Rico. Young people’s deaths spiked, surpassing the growth in the death rate among the elderly, despite the widespread belief that the hurricane only affected older people and those with preexisting conditions. Deaths from sepsis, a life-threatening complication from infection, rose nearly 44% to 325, compared to the previous three years; kidney-disease-related deaths rose nearly 43%, to 211.

On Sept. 13, 2018, Donald Trump described the official estimate of Irma and Maria-related deaths as a Democratic plot to make him look bad and claimed that the death toll was far lower. The president visited Puerto Rico for about four hours on Oct. 3, almost two weeks after the storm; according to the Demographic Registry of Puerto Rico, between Sept. 6, 2017, and the day Trump left the island, there were 640 more deaths than the average during the same period in the last three previous years.

In the absence of a comprehensive official list of victims, the stories collected here are the only source of information that can help explain the historic increase in mortality in Puerto Rico post-Maria.

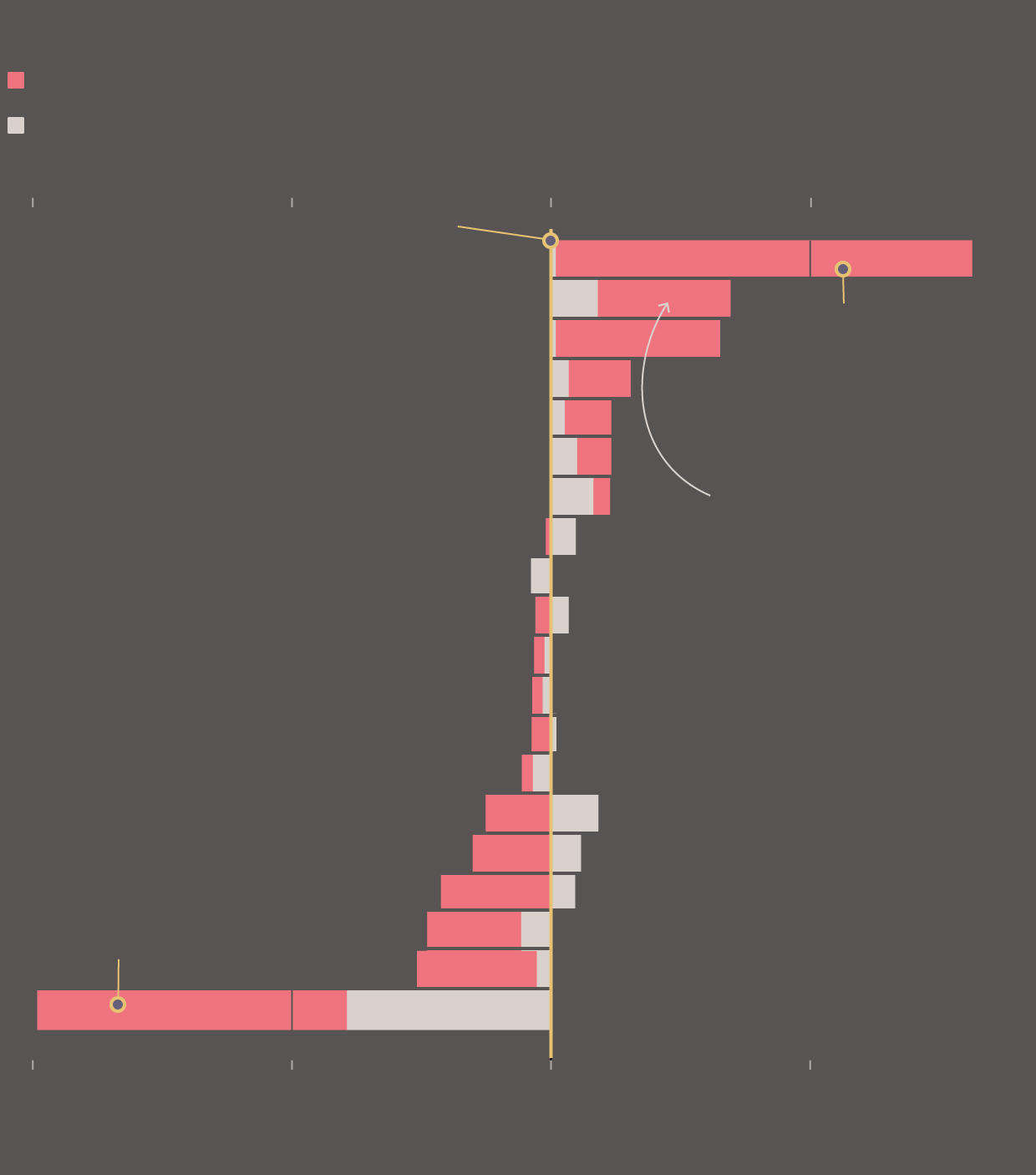

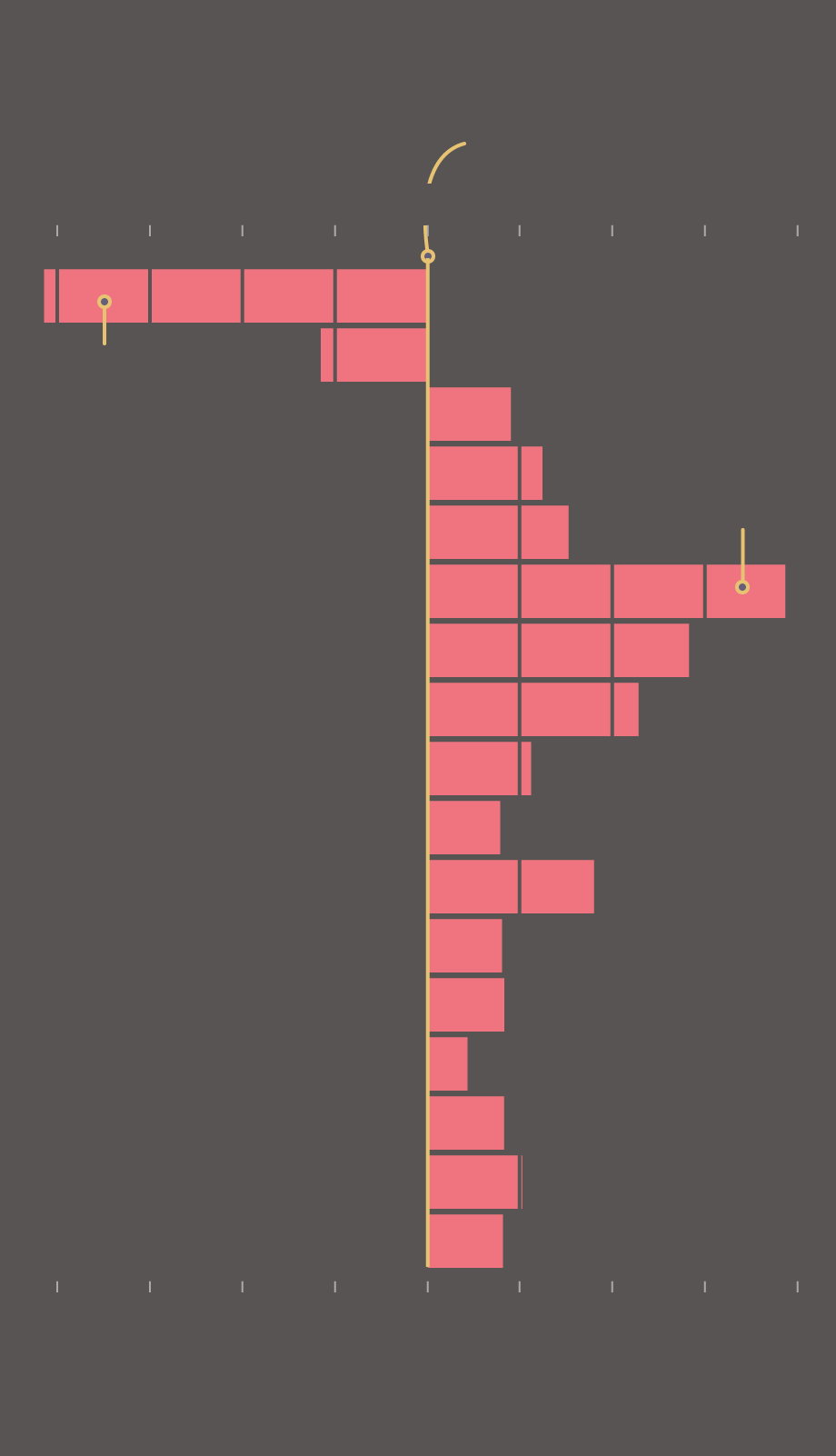

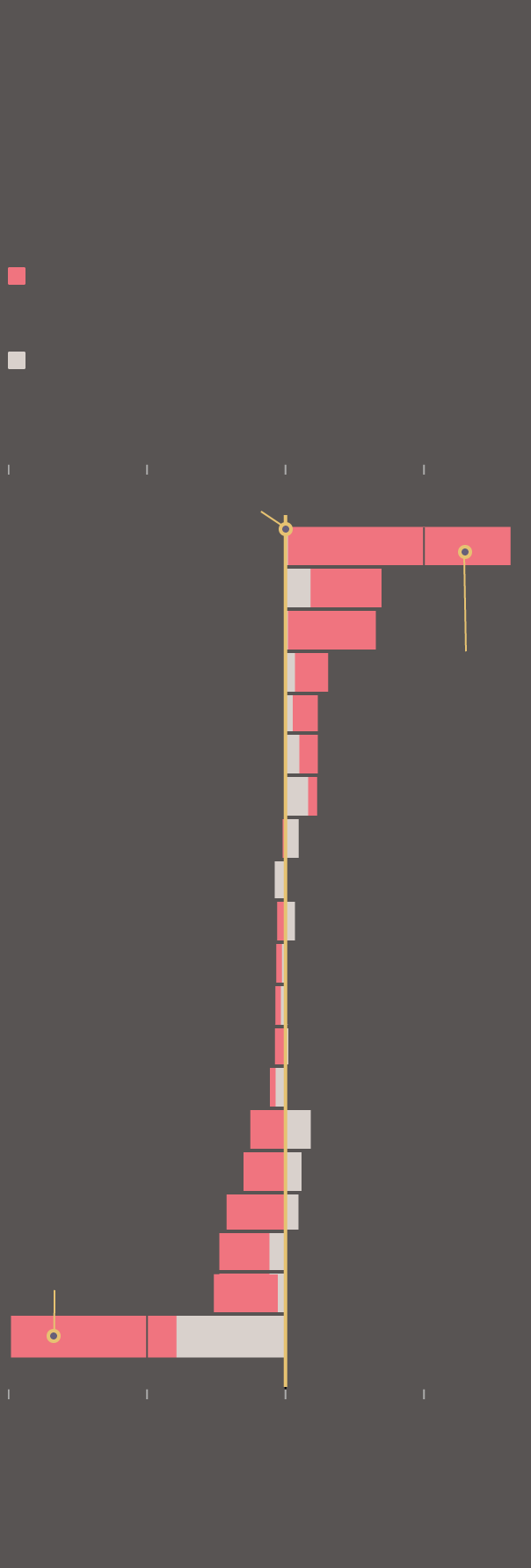

Hurricane-related deaths from Sept. 18 to June 2018

All deaths in Puerto Rico from Sept. 18 through Dec. 2017

The 2014-’16 average

share of deaths

Higher than

2014-’16 level

Complications of medical and surgical care

The share of people who

died from accidents, heart

disease, and diabetes

increased after Hurricane

Maria.

Lower respiratory diseases

Lower than

2014-’16 level

Data: Mortality data from Puerto Rico government, 2014-16, 2017

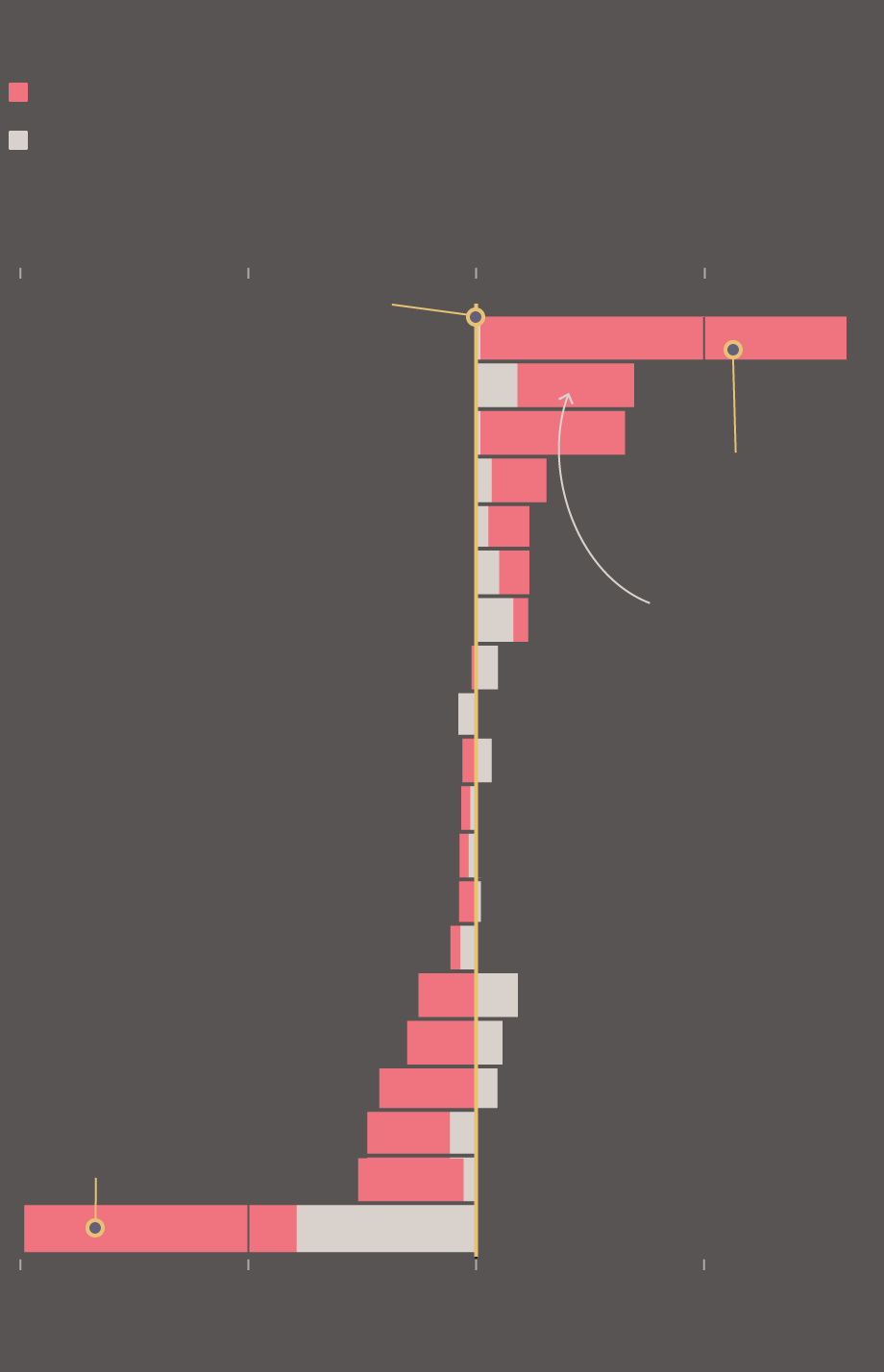

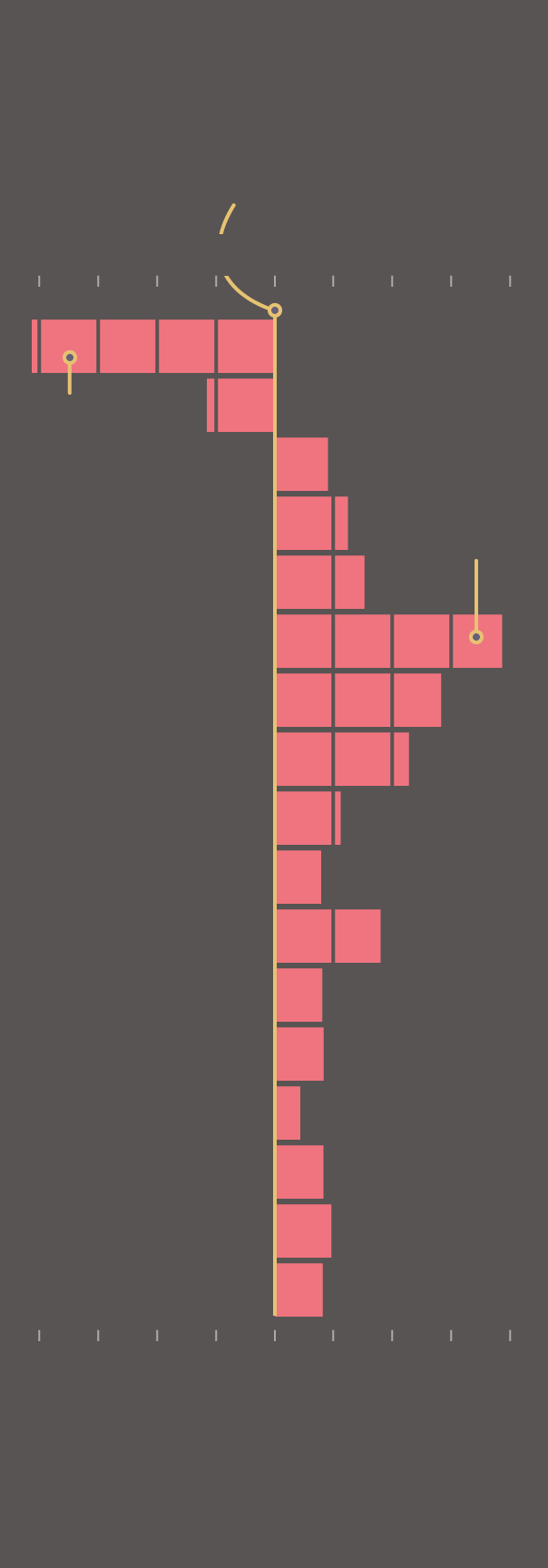

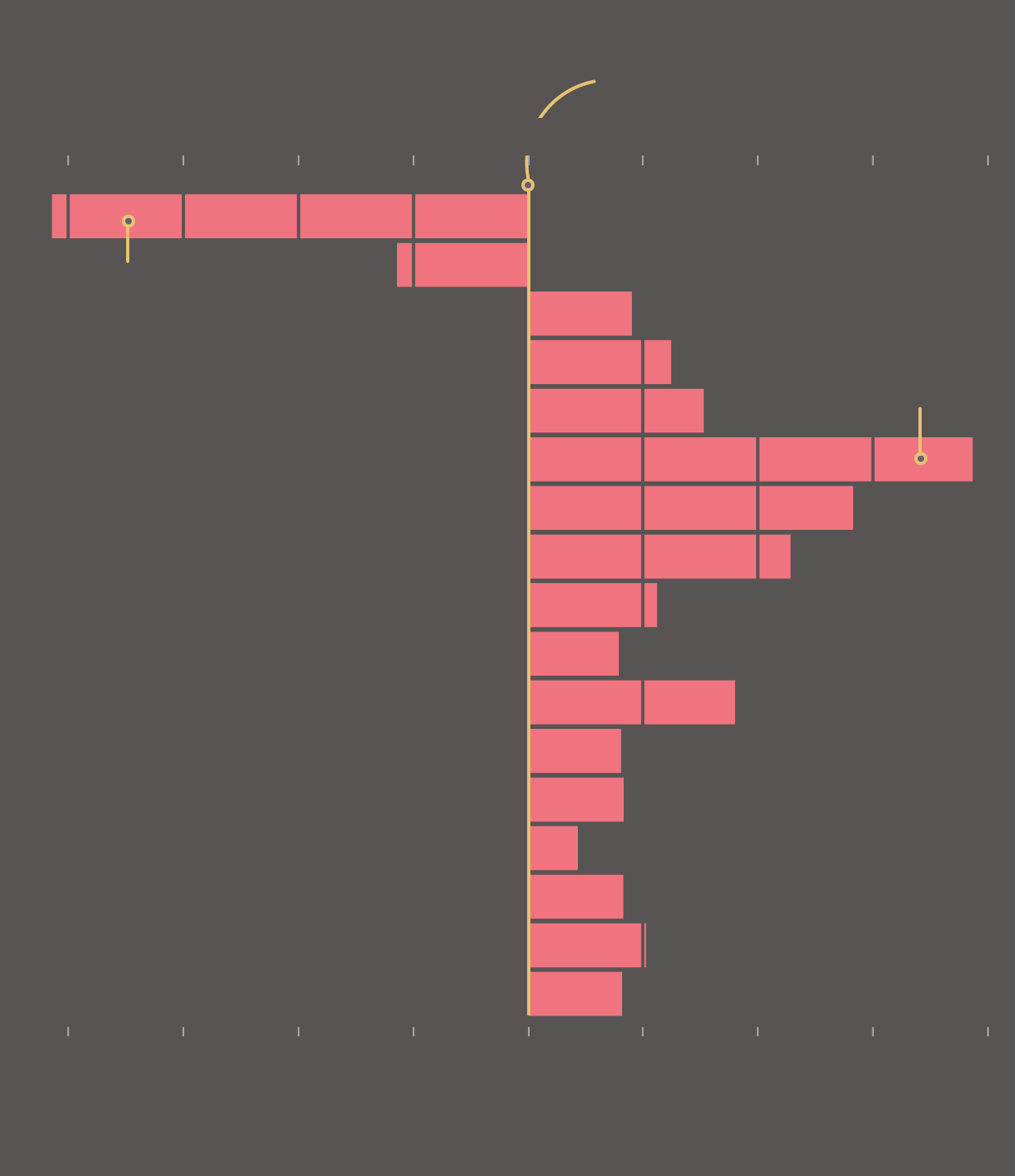

Hurricane-related deaths from Sept. 18 to June 2018

All deaths in Puerto Rico from Sept. 18 through

Dec. 2017

The 2014-’16 average

share of deaths

Higher than

2014-’16 level

Complications of

medical and surgical care

The share of people who

died from accidents,

heart disease, and

diabetes increased after

Hurricane Maria.

Lower respiratory diseases

Lower than

2014-’16 level

Data: Mortality data from Puerto Rico government, 2014-16, 2017

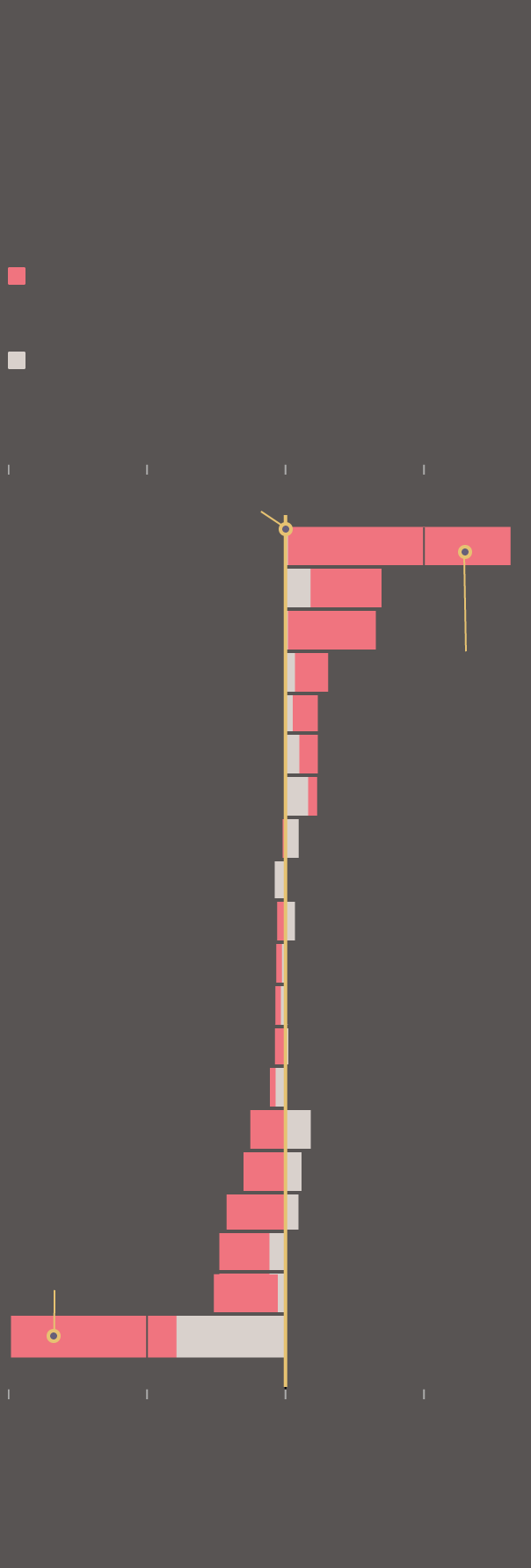

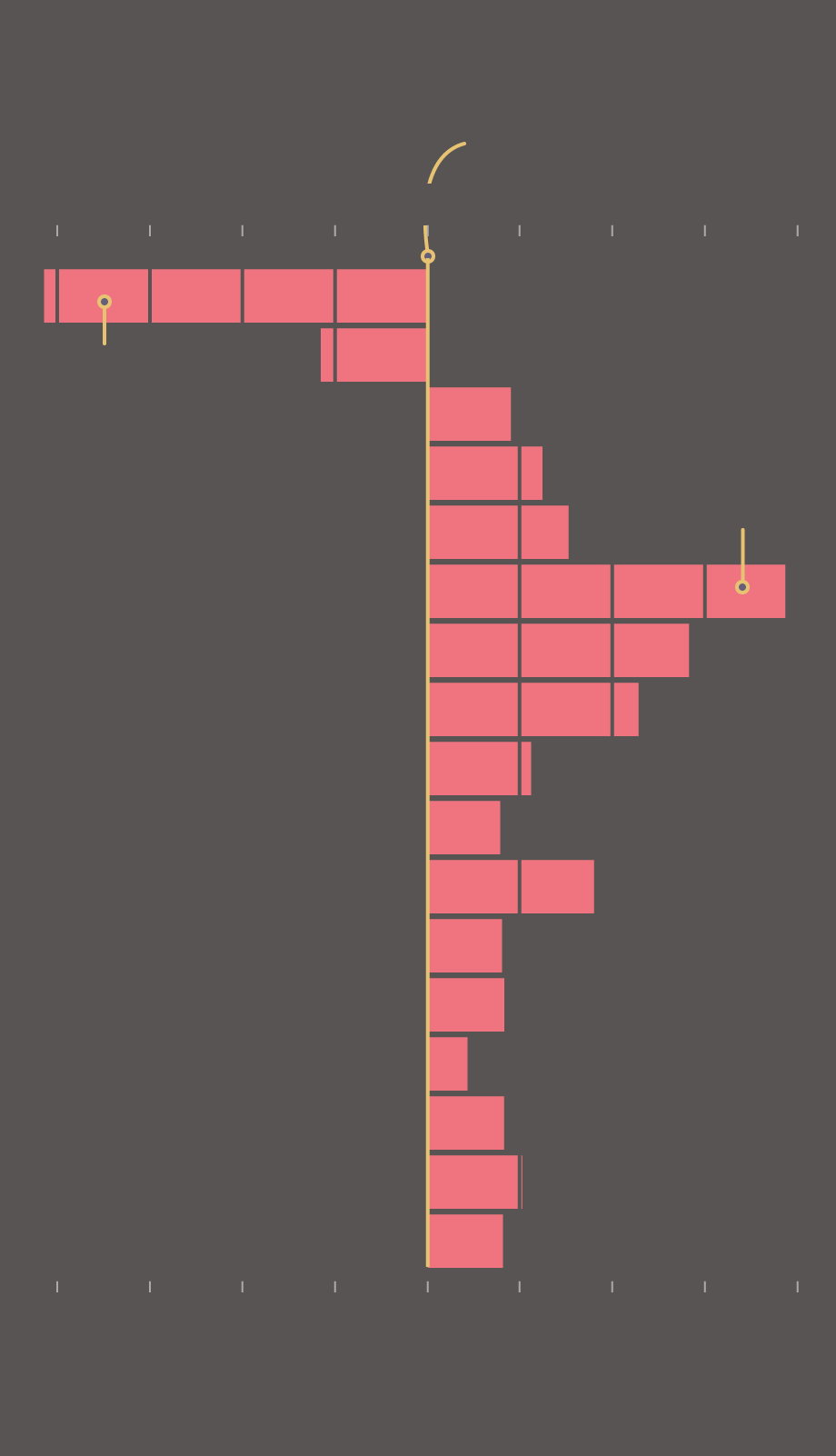

The share of people who died

from accidents, heart disease,

and diabetes increased after

Hurricane Maria.

Hurricane-related deaths from

Sept. 18 to June 2018

All deaths in Puerto Rico from

Sept. 18 through Dec. 2017

The 2014-’16 average

share of deaths

Higher than

2014-’16 level

Complications of

medical and surgical care

Lower respiratory diseases

Lower than

2014-’16 level

Data: Mortality data from Puerto Rico government,

2014-16, 2017

The spikes in deaths due to sepsis and kidney disease are red flags, but they’re only part of the story, as well as other causes of death which rose from 20% to 45% in the three months after Maria: pneumonitis, primary hypertension and renal hypertension, pneumonia and influenza, respiratory disease, Alzheimer’s, heart disease, and suicide.

Ramona González, 59, was bedridden due to a degenerative brain disease. In the heat after the hurricane, she started to develop bedsores and couldn’t turn on the air conditioning due to island-wide power outages.

Hospitals in San Juan admitted and released González twice, even though her relatives told doctors they were unable to treat her sores at home. They tried to get her aboard the Navy hospital ship, USNS Comfort. But patients had to be referred for treatment, and Ramona’s sister María says she never got the referral.

Ramona died of septicemia on Oct. 20, according to her death certificate.

“These are deaths that could have been avoided,” says Cruz María Nazario, an epidemiologist and professor at the Medical Sciences Campus of the University of Puerto Rico.

About half of the hurricane victims in our dataset died in hospitals, which saw a rise in mortality of 32.3%. Many hospitals lacked electricity. Those with generators often lacked the fuel to operate them, according to testimonies collected and observations made by CPI reporters. In dozens of cases collected by Quartz, CPI, and the AP, family members attributed their loved ones’ deaths to a lack of basic medical supplies and services like dialysis and oxygen. Others died in the absence of treatment for chronic diseases such as cancer, Alzheimer’s and diabetes.

Lack of electricitydeaths

Lack of access to medical caredeaths

Damages caused by flood, landslides, etc.deaths

Lack of access to communicationsdeaths

Lack of food or waterdeaths

The main mechanisms of death were self-reported by victims’ relatives who answered

an online survey launched by Quartz and CPI in December 2017. Here is a selected list of quotes from survey responses and follow-up interviews.

Puerto Rico has one of the highest rates of kidney failure in the US. Nevertheless, federal and local emergency plans classified dialysis as a relatively low priority, says Angela Diaz, executive director of the Renal Council of Puerto Rico, a non-profit that works to improve conditions for patients with kidney diseases.

Orlando López Martínez, 48, missed four days of dialysis because his treatment center in western Puerto Rico was closed after the hurricane. When it reopened, the center rationed dialysis due to shortages of generator fuel and freshwater. López got less than half his usual treatment.

“In the days after the storm he looked pale, yellowish, really bad,” said Lady Diana Torres, the mother of López’ 10-year-old daughter Paola.

He died on Oct. 10. The official cause of death was a heart attack brought on by kidney disease.

During Hurricane Maria, Puerto Rico’s Department of Health did not have an emergency response plan that told health institutions and patients what steps to take and where to go for help. Six months before the storm, Puerto Rico's government consolidated all its emergency response agencies into a single super-agency, the Department of Public Safety, without creating new protocols to replace the old ones. Past emergency response chiefs Epifanio Jiménez and Miguel Ríos have linked the island's poor disaster response to this abrupt structural change.

Underestimating the hurricane’s damage, the US military deployed a hospital ship, but not enough troops to rebuild critical infrastructure like communications and power lines, says Irwin Redlener, director of the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia University in New York.

“It would have been a perfectly appropriate job for the US military,” he says. “There’s probably no other agency in the world more capable than the US military in re-establishing communications, putting up a temporary electric grid, repairing bridges, making sure that access by ambulance is available.”

Officials from the Department of Health declined interview requests; a spokesperson from the US Defense Department was not able to respond to questions, citing preparations for Hurricane Florence. When ground commander Lieutenant General Jeffrey Buchanan was ordered to leave the island in November, he described the work of rebuilding as unfinished, citing Maria’s size and Puerto Rico’s isolation.

Three weeks after the hurricane, Saúl Pabey Martínez, 27, was electrocuted as he tried to connect a friend’s house to the electrical grid and fell off his ladder, says his mother, Doris Milagros Martínez. He died in the ambulance on the way to the hospital.

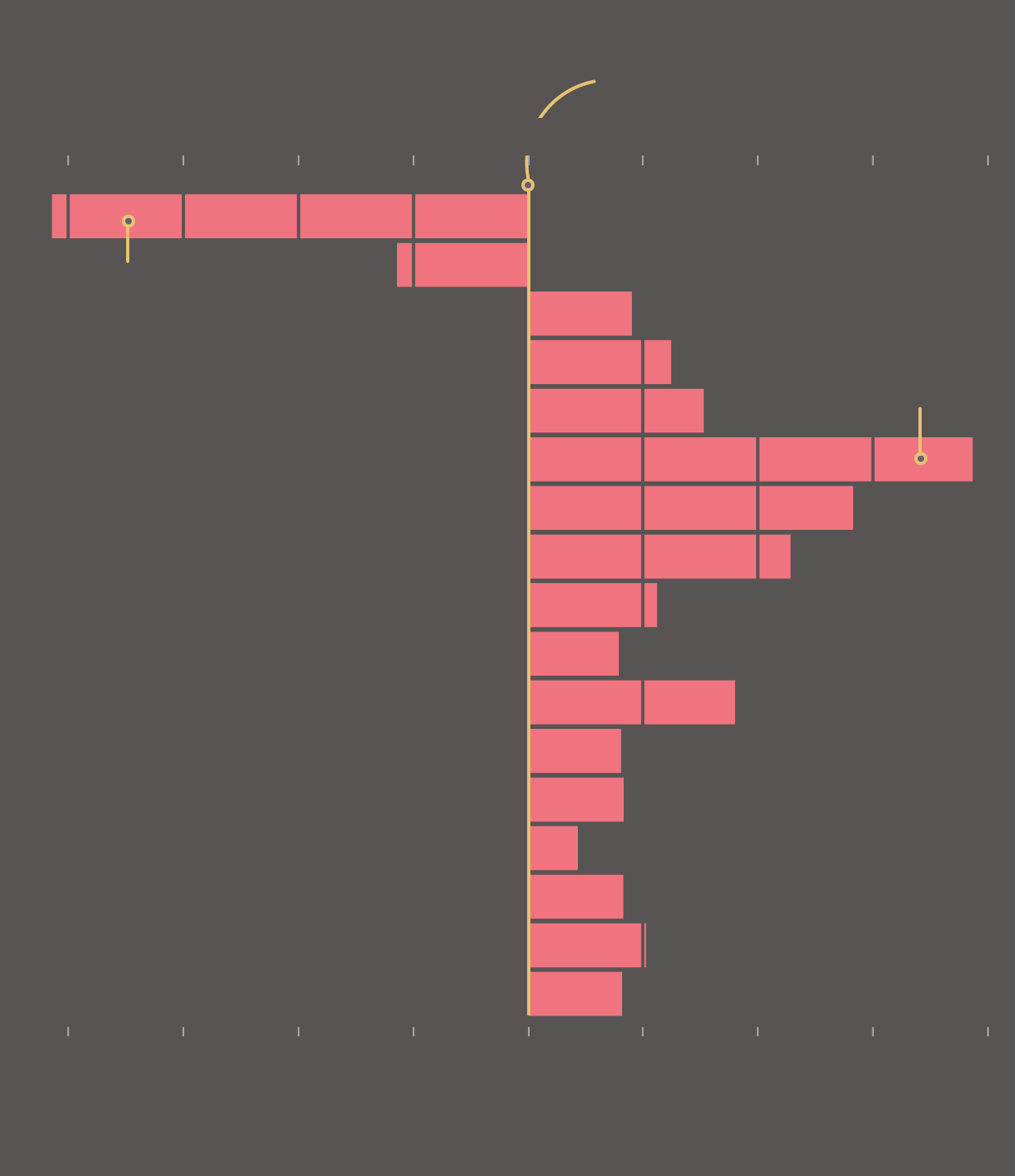

The number of deaths due to accidents spiked in Puerto Rico in the months after the storm.

Accidents and heart attacks were among the causes driving a post-Maria increase in deaths among adults between the ages of 30 and 44. One-fifth of deaths in this age group are still under investigation.

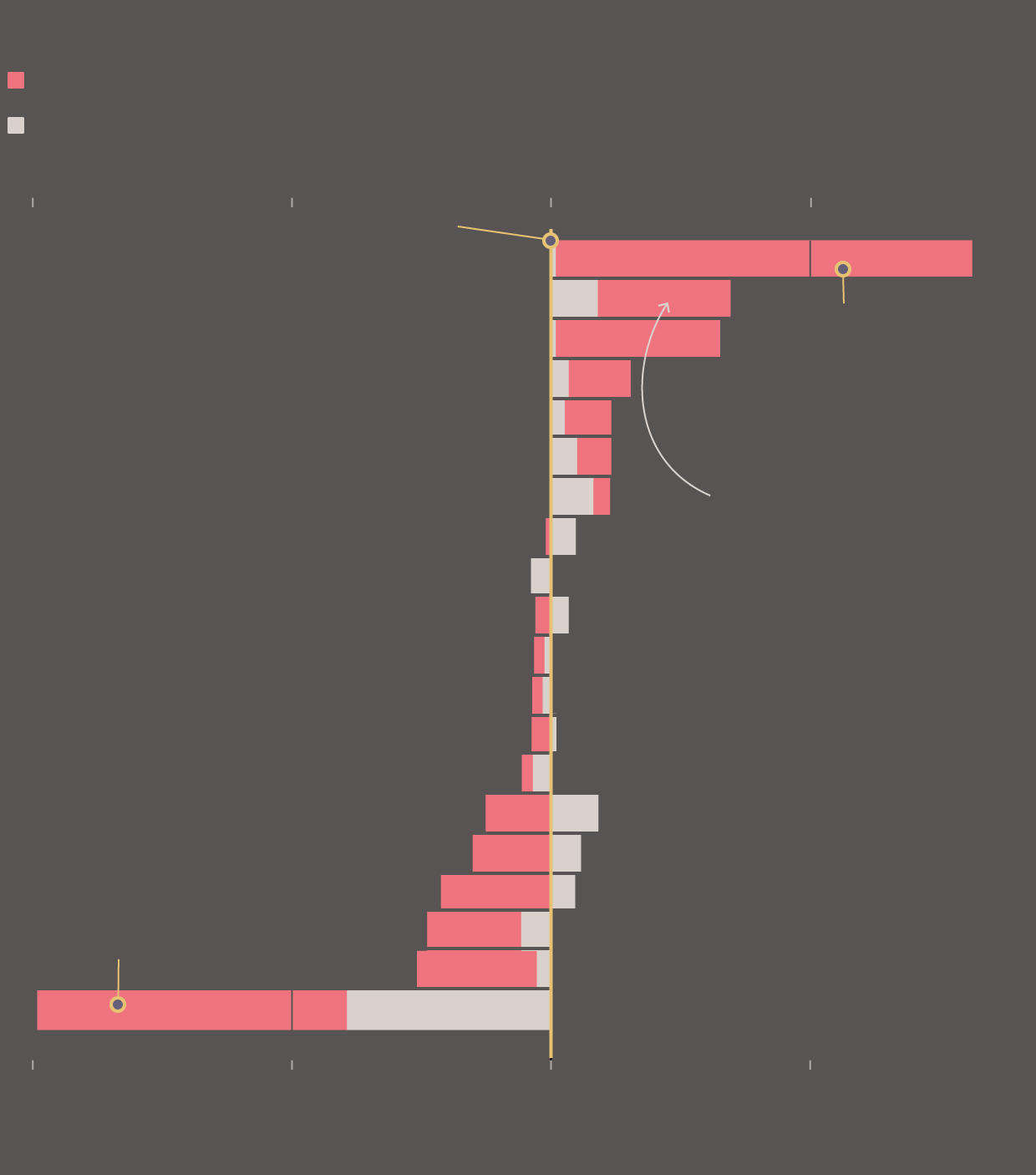

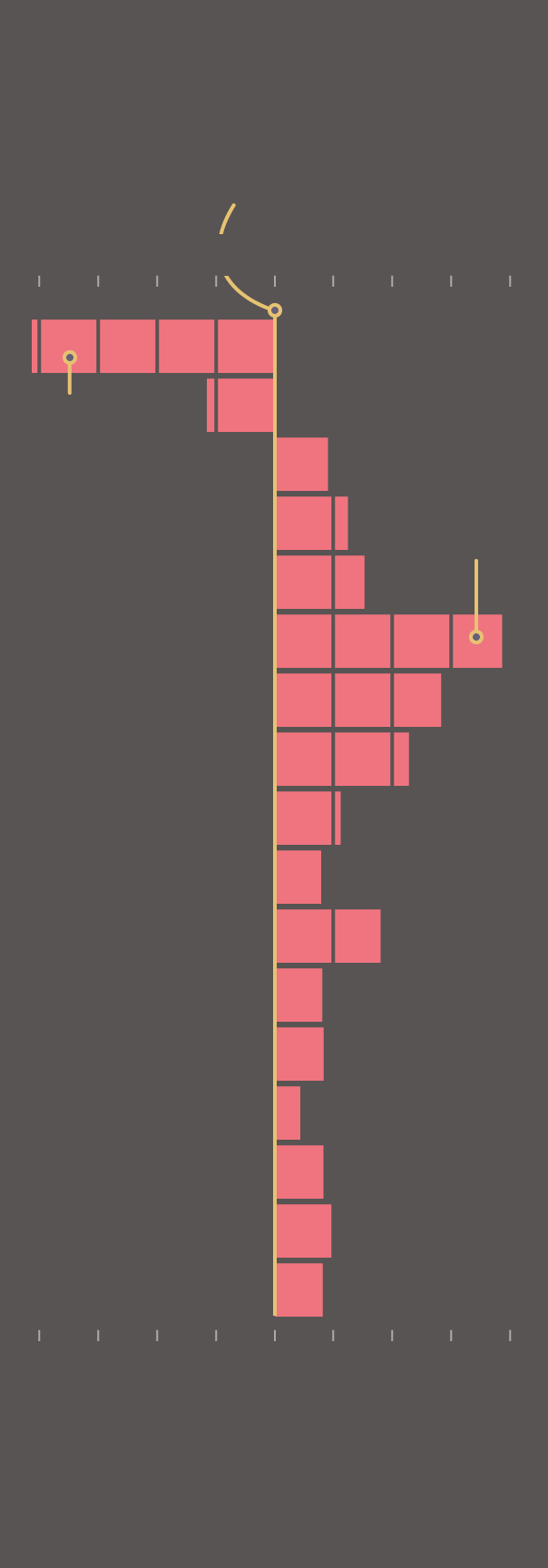

Death rates for most age groups increased after

the hurricane.

Death rate from September

to December, 2014-2016

The infant death

rate decreased 41%.

The death rate of 30-34-

year-olds increased 39%

in the last four months

of 2017.

*1-4, 5-9 and 10-14 year-olds are grouped together for statistical purposes.

Data and analysis: Raúl Figueroa Rodríguez

Death rates for most age groups

increased after the hurricane.

Death rate from September

to December, 2014-2016

The death rate of

30-34-year-olds

increased 39% in

the last four

months of 2017.

The infant death

rate decreased 41%.

*1-4, 5-9 and 10-14 year-olds are grouped together for statistical purposes.

Data and analysis: Raúl Figueroa Rodríguez

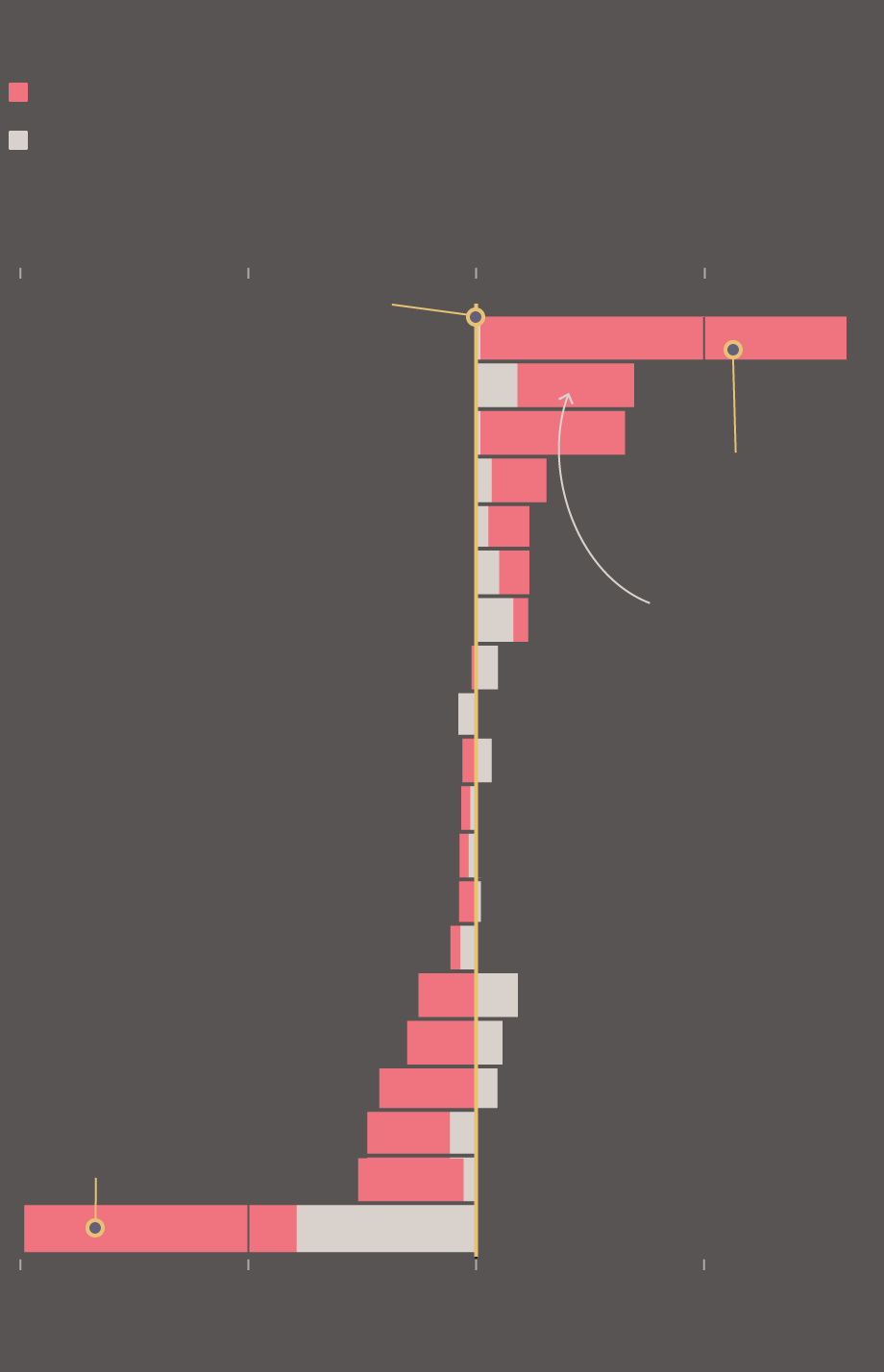

Death rates for most age

groups increased after

the hurricane.

Death rate from September

to December, 2014-2016

The death rate

of 30-34-year-

olds increased

39% in the last

four months of

2017.

The infant

death rate

decreased

41%.

*1-4, 5-9 and 10-14 year-olds are grouped together

for statistical purposes.

Data and analysis:

Raúl Figueroa Rodríguez

In a retrospective report, FEMA found it had underestimated the food and fresh water needed, and how hard it would be to get supplies to the island. Puerto Rico governor Ricardo Rosselló too has recognized his office’s bungled response, and promised new measures to avoid unnecessary deaths in the future, including a registry for the island’s most vulnerable residents.

But he also says the island is not ready for another Maria-sized event. The electrical grid’s collapse, which our investigation links to more than 150 deaths, is still just as vulnerable, Rosselló said last month. He declined to be interviewed for this story.

It’s also unclear whether the government itself is any better prepared. Puerto Rico’s Office for Emergency and Disaster Management has revised its emergency plan, but refused to provide a copy for review. Puerto Rico’s Department of Health has drafted a new public safety plan, but the agency did not respond to requests for a copy or for an interview. Waddy González, a FEMA official who oversees public health in Puerto Rico, said the plan has not been released to hospitals or to the public.

Although Puerto Rico’s government has acknowledged that many more people died than originally estimated, it has not released any analysis of the causes of mortality, nor updated the list of victims. Such data is vital to helping the island prepare for future catastrophic storms, say experts.

Before Maria struck, Puerto Rico’s doctors weren’t trained to record disaster-related deaths correctly. (The island’s health secretary, Rafael Rodríguez Mercado, along with the College of Doctors and Surgeons of Puerto Rico, argues it’s not doctors' responsibility to point out the non-clinical mechanisms that lead to death.) To improve data collection, Puerto Rico’s Institute of Statistics is pushing the government to adopt the Center for Disease Control’s standards for recording disaster deaths. On July 2, the Center for Investigative Journalism sued the Demographic Registry to force it to make all death records public.

Without better methods of recording deaths during an emergency, local and federal authorities run the risk of responding ineffectively to future disasters, says Mario Marazzi, the Statistics Institute director.

“Accurate death tolls matter because they save lives,” he says.